"Did you remember to update the DR?

If this question comes up regularly in your organization, your Disaster Recovery strategy is already broken.

Not because someone forgot, but because the question itself reveals the core weakness of most DR approaches.

If keeping DR functional depends on memory, checklists, or human discipline, then it is already failing.

What “we already have a DR” usually looks like in practice

In most organizations, saying “we already have DR” is usually true. A secondary environment exists. Some level of replication is configured. There is documentation explaining how recovery is supposed to work during an incident. From the outside, it appears thoughtful and complete.

The problem is not whether DR exists.

The problem is how it is treated as the primary environment continues to change.

In reality, production always comes first. Changes are designed for production, tested in production, and validated in production. DR is rarely included in the initial change flow. It is something teams intend to update afterward.

Sometimes that update happens right away. Sometimes it happens at the end of a sprint. Sometimes it gets delayed because another incident takes priority. Each delay feels reasonable on its own. Over time, those delays become routine.

That is the moment DR stops being a replica and starts becoming an approximation.

In many organizations, DR is not an active system. It is a calendared process.

It gets exercised during audits.

It gets reviewed when a customer asks for evidence.

It gets touched during scheduled DR tests.

Outside of those moments, DR is mostly dormant.

This is not because teams do not care. It is because DR is treated as something you return to, not something you operate. It lives on a calendar, not in the day to day change flow.

That creates a subtle but dangerous illusion. On paper, DR exists. In practice, it behaves more like a compliance artifact than an operational capability.

When DR is only revisited on schedule, it slowly decouples from reality. Changes continue to land in production. Assumptions shift. Dependencies evolve. Meanwhile, DR waits for its next reminder.

By the time a real disaster happens, DR is technically present but operationally unfamiliar. The system has not been exercised under real pressure. The people involved have not built muscle memory. What looked reliable during audits now depends on recollection, documentation, and hope.

And at that point, it is already too late.

“But we have automation for it”

Automation does not remove responsibility. It shifts it.

Most Disaster Recovery automation relies on declarative infrastructure code and pipelines that define how environments should look and how changes should be applied. This is an improvement over manual processes, but it does not address the underlying issue. Declarative code still needs updates. Pipelines still need to be maintained, exercised, and trusted. Someone still decides when changes propagate and whether DR stays aligned with production.

When automation is not part of the default production change flow, it becomes another system teams need to remember. Responsibility moves from manually updating environments to remembering to update code, trigger pipelines, and validate outcomes. The failure mode remains. It is just harder to notice.

Declarative code describes an intended state, not the actual state of a running system. When production is modified outside that declaration, even temporarily, the code is immediately outdated. If DR depends on that code, it inherits the same mismatch. Over time, emergency fixes applied under pressure accumulate, while the code and pipelines continue to exist as if nothing changed. They still execute, but they no longer reflect reality.

Pipelines introduce their own risks. DR pipelines are often treated as stable once they work. They are rarely exercised under real conditions, rarely updated as dependencies evolve, and rarely validated beyond planned tests. Meanwhile, cloud APIs change, permissions drift, and execution paths slowly degrade. A pipeline that is not continuously exercised and maintained cannot be trusted during an incident.

At that point, automation creates confidence without correctness. The system appears protected because it is automated, but the automation rests on assumptions that no longer hold. Automation that does not reflect reality is not protection. It is broken Disaster Recovery, written in code.

The solution is changing how DR is delivered.

A functioning DR strategy treats production and DR as two executions of the same system, not two systems that must be kept in sync. That starts with a single principle: keep one source of truth.

Not fewer lines of code, but fewer places where responsibility can diverge.

When production and DR are defined as separate stacks, separate folders, or separate pipelines, drift becomes unavoidable. Even if both are automated, responsibility has been duplicated. There are now two places to update, two execution paths to maintain, and two sets of assumptions that can slowly diverge. The failure mode is unchanged. It is simply encoded.

Instead, treat DR as an orchestrated variant of production. Use the same blueprint, the same modules, the same pipeline logic, and the same change flow. Then explicitly define the limited differences that must exist between regions, such as region identifiers, failover routing behavior, capacity decisions, or replication settings. These differences should be intentional, visible, and versioned, not discovered during an outage.

This is the shift: consistency by default, differences by design.

Once you make this change, DR stops being a separate project that needs constant attention. It becomes a controlled execution pattern. Changes are applied once and propagated through the same orchestration to both environments, with clear rules for what must remain identical and what is allowed to differ. That is how drift is prevented without relying on memory, checklists, or heroics.

Where Bluebricks fits: Consistent DR by default

Bluebricks was built around the assumption that drift is not a tooling failure. It is a delivery failure.

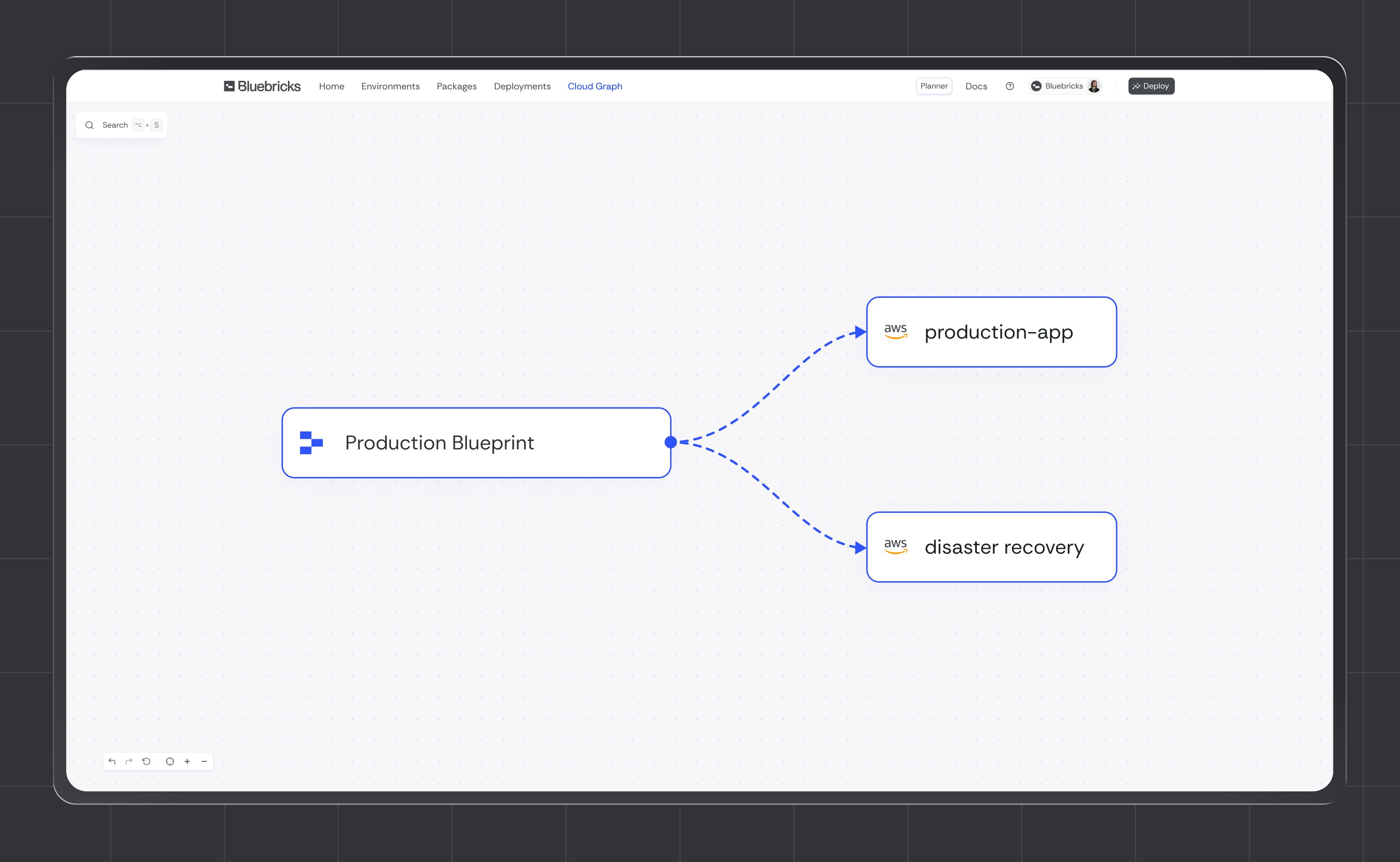

Instead of treating Disaster Recovery as a parallel system that needs to be synchronized with production, Bluebricks models DR as another execution of the same blueprint. The same infrastructure definition, the same orchestration logic, and the same change flow are used for both production and recovery environments.

There is no separate DR stack to maintain.

No duplicated pipelines to remember.

No second place where changes can silently diverge.

With Bluebricks, production and DR are driven from a single source of truth. Differences between regions are explicitly modeled as configuration, not copied into separate code paths. Region, routing, capacity, and replication settings are intentional inputs, not assumptions hidden in folders or pipelines.

Every change is applied once and executed consistently. If it runs in production, it runs through the same orchestration for DR. That means DR is continuously exercised as part of normal delivery, not during a quarterly test or a real incident.

This is what consistent DR looks like in practice. Not more processes. Not more checklists. Just fewer opportunities for drift.

Bluebricks does not ask teams to remember to update DR.

It removes the need to ask the question in the first place.